As Europe starts opening up to travelers again, it’s more exciting than ever to think about the cultural treasures that await. For me, one of the great joys of travel is having in-person encounters with great art and architecture — which I’ve collected in a book called Europe’s Top 100 Masterpieces. Here’s an ancient favorite:

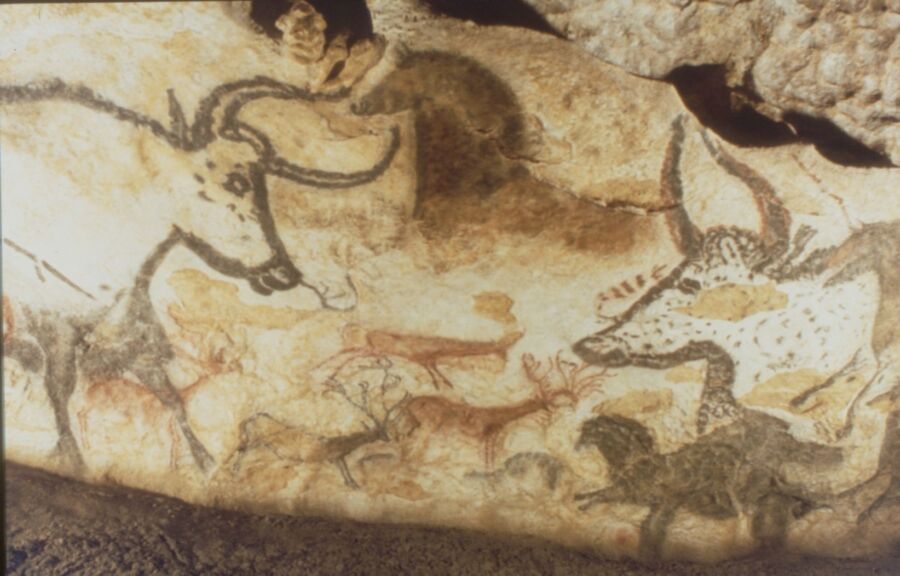

The caveman man cave at Lascaux is startling for how fashionably it’s decorated. The walls are painted with animals — bears, wolves, bulls, horses, deer, and cats — and even a few animals that are now extinct, like woolly mammoths. There’s scarcely a Homo sapiens in sight, but there are human handprints.

All this was done during the Stone Age nearly 20,000 years ago, in what is now southwest France. That’s about four times as old as Stonehenge and Egypt’s pyramids, before the advent of writing, metalworking, and farming. The caves were painted not by hulking, bushy-browed Neanderthals but by fully-formed Homo sapiens known as Cro-Magnons.

These are not crude doodles with a charcoal-tipped stick. The cave paintings were sophisticated, costly, and time-consuming engineering projects planned and executed in about 18,000 BC by dedicated artists supported by a unified and stable culture. First, they had to haul all their materials into a cold, pitch-black, hard-to-access place. (They didn’t live in these deep limestone caverns.) The “canvas” was huge—Lascaux’s main caverns are more than a football field long, and some animals are depicted 16 feet tall. They erected scaffolding to reach ceilings and high walls. They ground up minerals with a mortar and pestle to mix the paints. They worked by the light of torches and oil lamps. They prepared the scene by laying out the figure’s major outlines with a connect-the-dots series of points. Then these Cro-Magnon Michelangelos, balancing on scaffolding, created their Stone Age Sistine Chapels.

The paintings are impressively realistic. The artists used wavy black outlines to suggest an animal in motion. They used scores of different pigments to get a range of colors. For their paint “brush,” they employed a kind of sponge made from animal skin. In another technique, they’d draw the outlines, then fill it in with spray paint — blown through tubes made of hollow bone.

Imagine the debut. Viewers would be led deep into the cavern, guided by torchlight, into a cold, echoing, and otherworldly chamber. In the darkness, someone would light torches and lamps, and suddenly — whoosh! — the animals would flicker to life, appearing to run around the cave, like a prehistoric movie.

Why did these Stone Age people — whose lives were probably harsh and precarious — bother to create such an apparent luxury as art? No one knows. Maybe because, as hunters, they were painting animals to magically increase the supply of game. Or perhaps they thought if they could “master” the animal by painting it, they could later master it in battle. Did they worship the animals?

Or maybe the paintings are simply the result of the universal human drive to create, and these caverns were Europe’s first art galleries, bringing the first tourists. While the caves are closed to today’s tourists, carefully produced replica caves adjacent give visitors a vivid Stone Age experience.

Today, visiting Lascaux II and IV, as these replica caves are called, allows you to share a common experience with a caveman. You may feel a bond with these long-gone people…or stand in awe at how different they were from us. Ultimately, this art remains much like the human species itself — a mystery. And a wonder.