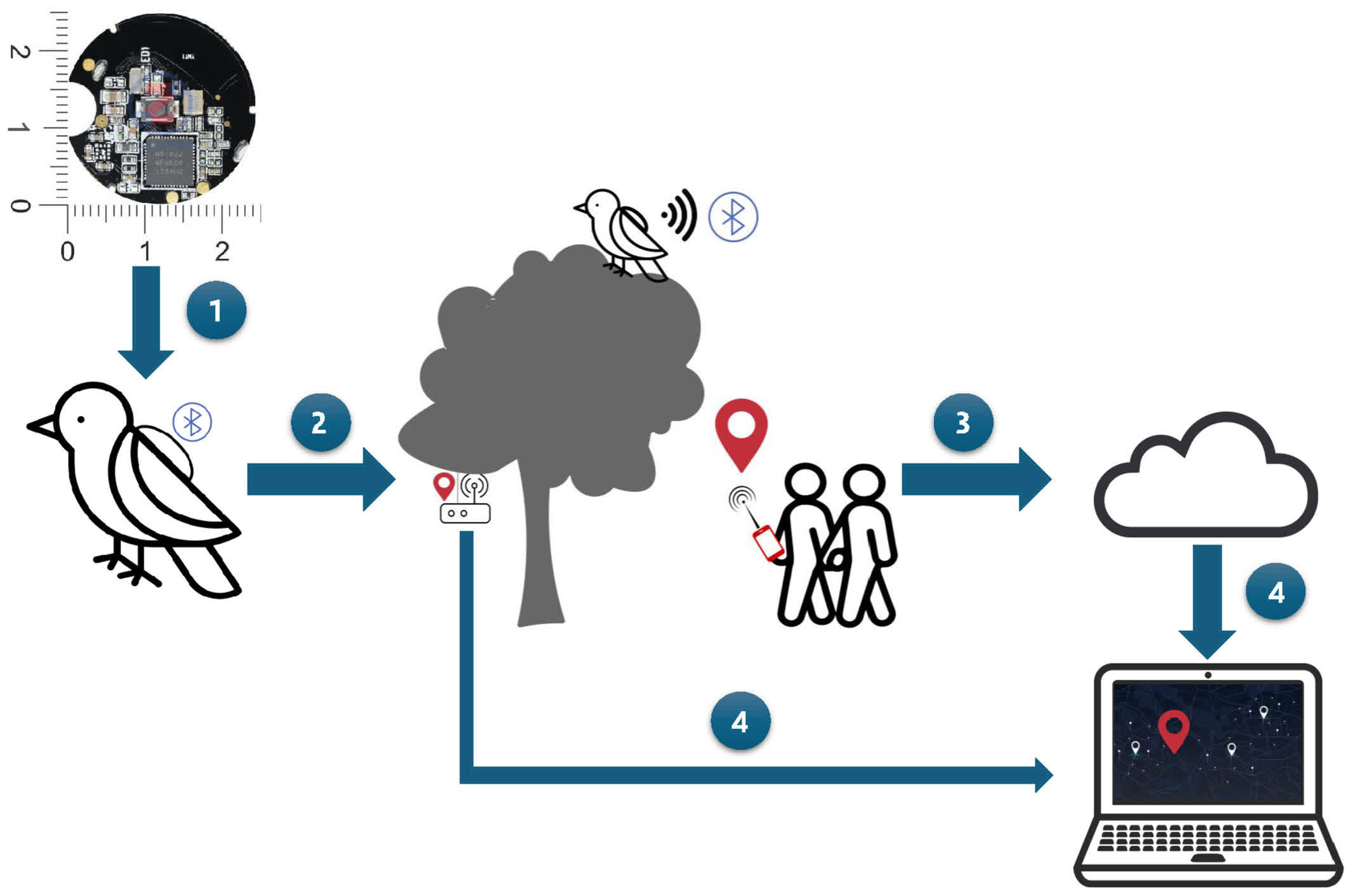

Why it matters: Usually, tracking wildlife involves using GPS trackers, which are expensive and power-hungry. However, researchers have begun utilizing tiny AirTag-compatible trackers that broadcast an animal’s location by pinging nearby mobile devices.

Conservationists’ newest weapon is a simple $7 Bluetooth beacon in a 3D-printed case. Thanks to the relatively uncomplicated hardware, it weighs much less than GPS trackers. Wildlife should barely notice they are wearing the device.

A Nordic Semiconductor nRF5 chip powers the tracker, flashed with firmware to broadcast as a Bluetooth low-energy beacon. It generates a key compatible with Apple’s Find My network, meaning the trackers can piggyback on the vast, crowd-sourced network of iOS devices already out in the world. Any iPhone within range of a beacon can anonymously report its position to researchers.

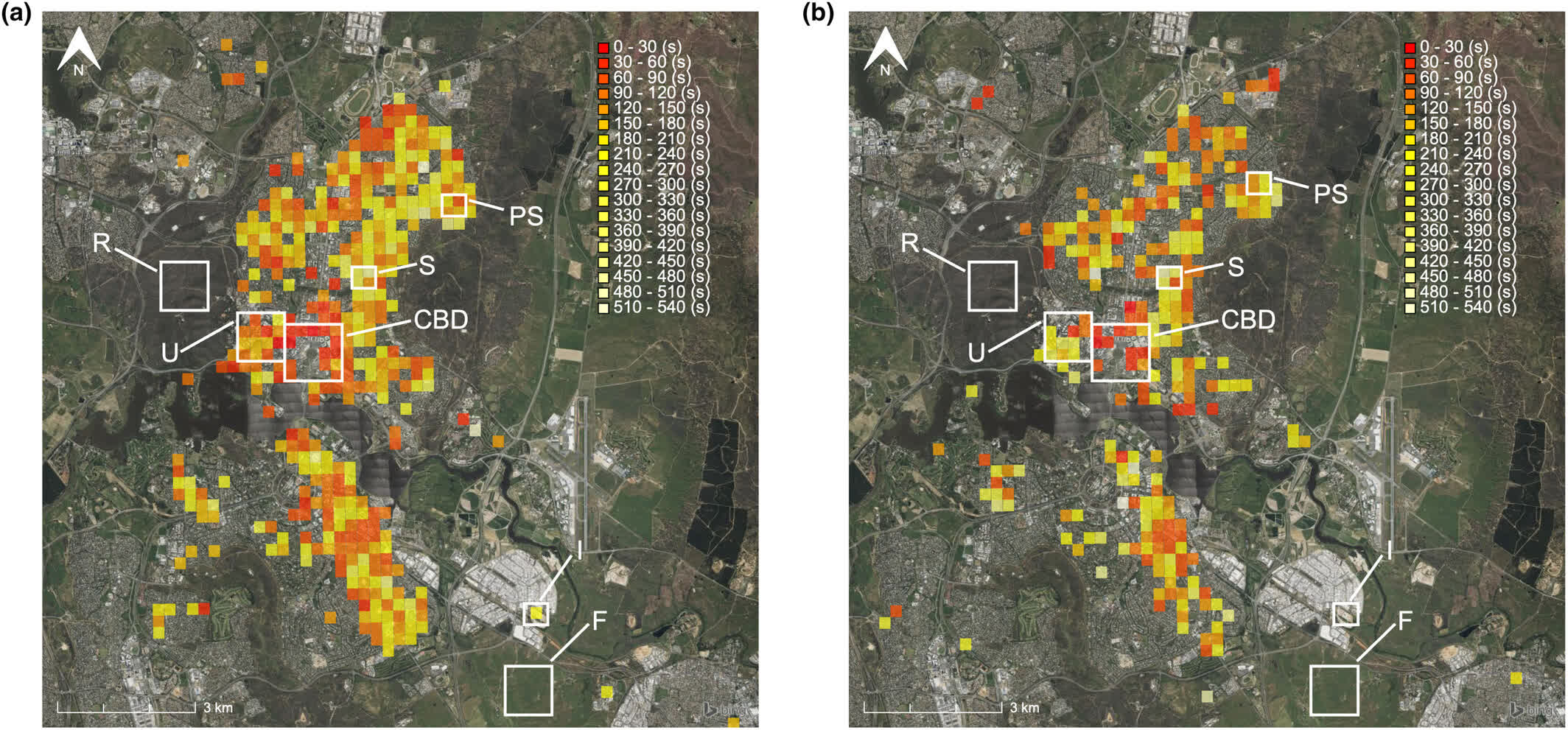

Researchers from the University of Zurich and the Australian National University deployed beacons around Canberra, Australia, to test their system. They found that while not as precise as GPS, the BLE beacons achieved positioning accuracy within about 100 meters, which is not bad considering the minuscule cost and power requirements. Performance was even better for calculating the relative positions between multiple beacons, which is crucial for studying animal interactions and spatial relationships within packs or herds.

The devices are cheap and easy enough to deploy that wildlife researchers can equip entire populations of animals, even in remote areas. It also requires no hands-on tracking or recoveries.

Furthermore, the more BLE beacons the researchers deploy in the wild, the more mobile devices pick up the signals and report locations to the central base. Unfortunately, the trackers become much less effective in sparsely populated areas. Researchers may be able to overcome this caveat with a network of receivers built with Arduino, Raspberry Pi, or ESP32 boards.

There are other limitations, too. The researchers note that BLE beacons are generally prone to “high positional error.” The presence of busy roads seems to deteriorate precision, likely due to interference or signal blocking from all the vehicles. The tracker’s 100-meter accuracy will also not suffice for more precise studies. Still, these trackers could be a game-changer for applications where the sheer scale of tracking is the biggest obstacle.

Image credit: Stefan Schwinghammer